|

|

|

|

|

|

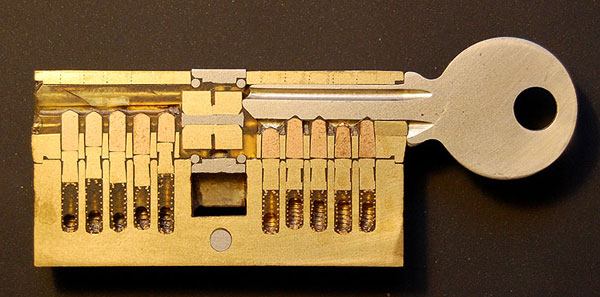

The real thing, in cross-section |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Being a geek, Iíve had from childhood that

ingrained curiosity to find out what makes things tick:

plants, animals, machines, they all had to be understood. These days

there seem to be ever more tools catering to this need virtually:

web sites abound with photos, diagrams and explanations; museums are

full of lovely scale models and computer visualizations. But though

these can all help, to my mind they can never replace the three hands-on methods for

teaching people an objectís function and design. The first method is to let them handle the object, up close and personal, and examine it directly: feel it, knock on it, peer into it, weigh it in their hand and watch it in action. If the object is a common one -- like a bicycle, or a turtle, or a light bulb -- this is easy to do at home; for other items -- a dinosaur, or a brain, or a spaceship -- you need a museum of the kind that shows you not a picture of the object, nor a plastic scale model, nor a movieÖ but the real, actual thing itself. The importance of this canít be overstressed. |

|

|

|

Click a photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

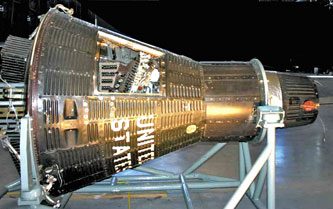

For instance, Iíve seen many models of spacecraftÖ and a few real vehicles that have returned from space. The models are usually small and schematic, with flat panels replacing the rich complexity of the original components. What can you get from such? Looking at a real Mercury capsule you can see the full story: the materials used tell of the fierce necessity to reduce weight; the eroded surface recalls the intense heat of reentry; the thin outer skin drives home the incredible courage of the man who sat in there alone, waiting to be blasted into space. And if itís a Soviet ship, you can see the many small differences in engineering, odd instruments with Cyrillic labels... yet converging on the same result. No Plexiglas model can give you this level of understanding. Nor can it give the jolt I got on seeing that warning stenciled on a Soyuz reentry module: ďMan inside! Help!Ē -- a testimony to both the danger of the landing and the ignorance that may compound it... |

|

|

|

Lastly, you need to provide a cross-section

of the actual object. This

allows one to really grok the relationships of all the parts. A good

cross-sectioned unit is a work of art; one must retain enough of the

original structure to give context while showing the innards in all

the important places. If the resultant unit still works, so much the

better; you then have a Demonstration Unit of your object. Producing a top-notch cross-section often takes as much skill as making the original device in the first place. Itís not something you normally do at home (you can see in the photo below the closest I came myself -- a section of a cylinder lock and key, produced in my lab at work using some vacuum gear, epoxy cement and metallographic polishing gear). A museum can cope with this best; the Deutsches Museum in Munich has a cross-section of an Airbus -- a huge annular slice two seats deep... and Natural History museums can afford to mount biological specimens with the required cutouts. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click a photo to enlarge |

|

|

|

Unfortunately, many technology and science museums seem entranced by the glitter of multimedia alternatives to the real thing. And so, you can go to a museum and see an entire floor dedicated to Genetics and Ecology with wall to wall displays of the code -- CAG GAT TAC GGA ... -- and huge stylized double helices of plastic, and murals of animal photos, and videos about the danger of extinctionÖ all commendable, but all second hand experience. If you want to show me DNA, then show me DNA -- in test tubes, or through a working electron microscope I can peer into. If you want to discuss the eco-suicide weíre so stupidly committing, display a real Dodo (a dead one), or a passenger pigeon, which will drive home the issue better than any graphic. If itís the process of evolution you describe, show us those finches with their beaks -- real ones, dead or alive. It worked for Darwin; it will work for us. |

|

|

|

The incredible diversity was there; the interrelations of

species through the evolutionary tree were starkly visible in the

comparative anatomy of their bones; the preciousness and fragility

of life was brought home by the loss of species that were once

hunted and stuffed so nonchalantly (and, yes, they had a Dodo too). Lastly,

the incredible biotechnology of the animal machine was clearer than

Iíve ever seen it before, since these creatures had been taken apart

for me, showing their bones and dentition, so I could see how the

vertebrate body scheme works and adapts to different eco-niches (we

all heard that the horse had lost some toes, but I had to see them up close to realize that its long

lower leg bones are fused from analogs of those in our hands and

feet). Or consider a turtle -- ever wondered how its shell connects

to its spine? (Actually, theyíre

completely fused at the back).

Sure, a plastic model of a skull can give you the high

level structure, but it canít possibly convey the exquisite

detail of the natural specimen... Iím not saying we should pickle armies of beasts; Iím not saying multimedia and models arenít useful, either; but I do say that we should also strive to show people, young and old, the outside and the inside of real objects from nature, science and technology. Young kids who feel the wonder of it all will be captivated and will go far. Older ones who are already hooked will learn more and have a whopping good time. And those unfortunates who won't understand what the big deal is, the kind that will treat a real lunar rock as if it were just a gray lump of stone, can stay home and watch the commercials on TV.

Photo credits (all under Creative Commons license): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home | HOC | Fractals | Miscellany | About | Contact Copyright © 2008 N. Zeldes. All rights reserved. |

|